God is Dead, But His Kingdom Still Resides Inside You

How philosophy and theology combined to produce a spiritual atheism that could serve us well in the 21st century.

“The Kingdom of God is within you” and “God is dead” are two seemingly contradictory phrases that have long resonated with my feelings on religious belief, and through which I can perhaps best explain my spiritual atheism and the journey that brought me here.

Like many, as a child I listened and blindly absorbed the usual biblical tales in school assemblies, at church on the rare occasion I attended – usually under duress – and in illustrated junior versions of the bible at home. I heard and understood the message of the Good Samaritan; I stared in awe at this man Jesus, son of God, draped over a cross, bloodied and beaten, and wondered at the strength of character and faith to voluntarily accept such a fate; and I adopted the belief that heaven awaited me if only I behaved in a Christian manner. I was, to all intents and purposes, a believer, a Christian.

But then, again like many others, I developed other interests such as a fascination with fossils, dinosaurs and human history, and eventually realised the cognitive dissonance required to hold both ideas as simultaneously true. Where were the great lizards referenced in the Bible? If we evolved from apes then how could God have crafted the first humans? If miracles are real then why do they no longer seem to occur? I had become an atheist before the age of 10.

Nor was I a kind, benevolent atheist. I scoffed at believers, especially literal believers who saw the bible as an accurate historical record. I despised anyone who needed religion or a book to explain to them how to be good, or for whom the threat of eternal damnation was the only barrier to being bad. I accepted the role of religion as a source of hope for those living in dire situations, such as poverty stricken third world countries, but for those in the West the church was simply exploiting their naive weakness and they deserved it for being so stupid.

Maintaining these views well into my twenties, I also developed a fascination with theology itself. Why was some form of religion present in almost every single human society we know of? How could so many variants of ultimately the same type of belief system (an omnipotent unseen creator that rewards or punishes behaviour on Earth) form independently in every corner of the globe? Why was Christianity so successful, even though it required vast armies and extensions of power to achieve its aims? Why were no Western leaders openly atheist in an age where science has all but disproved the theory of a creator? Why was something so obviously (to me) untrue still held in such high regard by so many, including most of our beloved institutions and rituals?

But the biggest question, formulated when I was around fourteen years old and still plaguing me nearly three decades later, was this: what role does religion play in maintaining our society, and what will happen now that Western religiosity is in dramatic decline, at least in terms of literal belief and declining church attendance? At the time I talked about the ‘moral fabric of society being ripped away with nothing to replace it’ and wondered if this accounted for the declining standards in behaviour discipline, manners and respect that I saw amongst my peers – at least in comparison to how I was raised, but also to the halcyon vision of Britain I had mentally constructed from literature and movies.

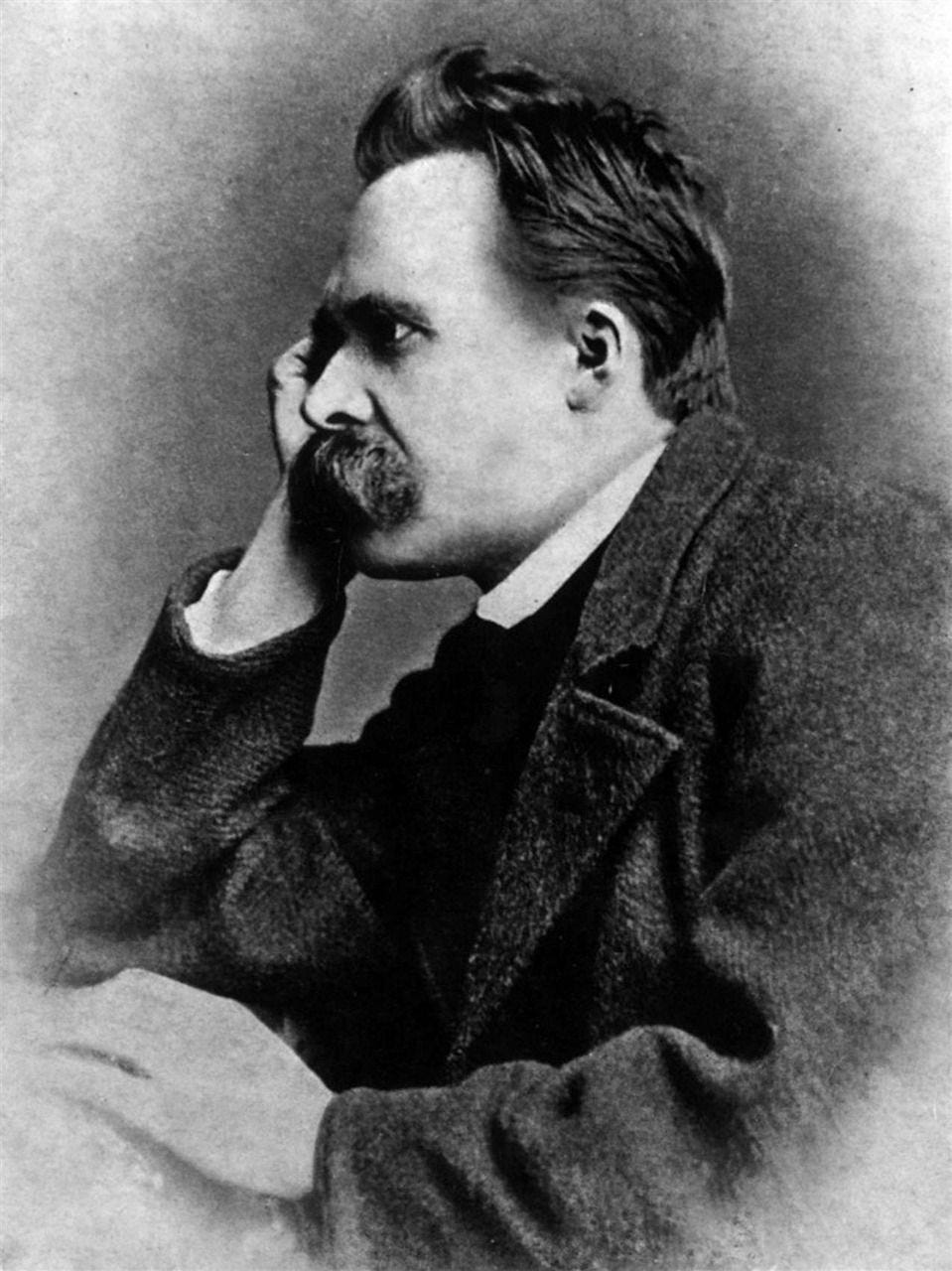

I had no experience of philosophy until my late twenties, at least not in a direct and conscious way, when I found myself spending several evenings a week drinking wine and smoking on the veranda of a new build care home in Bristol where I was caretaker. The night shift workers would regularly join me on my breaks, and one in particular, John, became a good friend for a while. He listened to my frustrated ramblings on the futility of religious belief, sighed, and told me to read Nietzsche. At this point I did not even understand what the field of philosophy covered, but I duly ordered a copy of Thus Spake Zarathustra and got stuck in.

Immediately the phrase that jumped of the pages at me was “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.” As the great German thinker proceeded to develop an idea that man is merely the tightrope, or stepping stone, to the Übermensch – a breed of man capable for forging his own values without the need for rules and guidance – something clicked inside my brain, and a fuller picture of religion, faith, and morality started to form from the mass of confused thoughts. Here was the validation for my own stance, from the pen of one of the West’s greatest minds 150 years earlier, that there is no God and the Christian faith is fundamentally flawed. Atheism confirmed.

Yet I was unable to abandon the other great quote that I had retained from childhood, that the ‘Kingdom of God is within you’. For all the dismissals of the bible, I still found myself stirred by hymns, awed by church architecture, inspired by Milton, Blake and Dante. There is something unmistakeably spiritual about these aspects, even considered from an atheist perspective. It is easy to see how people were compelled by the magnificence and grandeur of it all to obey, to live in fear of judgement, to forgive its excesses as a manifestation of the glory of God. I was an atheist with a God shaped hole.

This merely led to me explore faith even further, and perhaps the greatest contributor to the journey was the (somehow) controversial psychologist-cum-philosopher Jordan Peterson’s video series exploring the bible stories from a Christian but metaphorical perspective. I began to understand how much wisdom is packed into these tales, about the human condition and ways to understand and manage the world around us. The real reason it has such value for believers was not that they were blindly taking it as a literal historical record, but that each story contained a moral and often psychological analysis of a problem with advice on how to deal with it. Even down to prayer, which had always seemed like a legitimised form of schizophrenia to me, was suddenly a ritual that had deep purpose, orienting the individual towards a goal and encouraging the synthesis of thoughts into a coherent statement – this is a healthy practice for anyone regardless of faith and we find it manifesting in other forms such as journalling or, in my case, ranting in the shower each morning.

The final step to understanding my beliefs, or perhaps better to say to clearly synthesising them, came recently when my children began asking me whether I believed in God. A tricky one, as they all attend Catholic or Church of England schools (a decision we made with a view to them receiving a sound, moral education as a start in life) and have no desire to send them to school espousing views that may offend teachers and other students – but at the same time I want them to think critically and have the confidence to challenge authority (politely). Tricky also as I had not spoken about my beliefs much, they were still a maelstrom of thoughts and ideas that had some abstract meaning that I now needed to convey to four children under ten.

Firstly, I pointed out that these are my own opinions and beliefs based on my lifetime’s accrued knowledge and experience, and in no way was I trying to tell them what to believe nor indeed was I certain that my beliefs were correct. I also stressed that faith is personal and we all have our own understanding of and use for it, therefore it is important to respect the opinions of others even if we disagree or do not understand. Our aim is to raise young people who have conviction in their own beliefs because they have given them due consideration, whilst being receptive to and tolerant of differing views.

Secondly, I told them that I do not believe in an actual God that created the world, because I believe in evolutionary theory, the fossil record etc., and that I believe the concept of God was created a long time ago to explain the as yet unexplained in the natural world around us. That is why we find some form of worship to a higher power in all civilisations and societies, it provides comfort, reason and stability in a world full of often horrific and terrifying ordeals, from natural life processes such as death to great natural occurrences such as storms, floods and fires. This is not to say that I necessarily subscribe to a Hobbsean view of human nature, but our environment itself can be frightening in its own power and destructive capacity. I suggested that God could be understood as ‘nature’ in this way, an idea I latched onto when reading Spinoza’s Ethics, in which he suggests the two terms are interchangeable.

Thirdly, Jesus was probably a real person but I do not believe he was actually the son of God or a miracle pregnancy (I will never not think it most likely that Mary had been a naughty girl!). The tales of his great deeds could as easily have been lies at the time as myths developed later. But that is not to say that the general message of Jesus is not a good one, or that his teachings and those of the Bible would not stand us in good stead. In fact if we all aimed to live a ‘Christian life’ on the whole the world would be a pretty decent place. His role as a symbol of self-sacrifice is probabaly the most powerful and effective motif of the last two thousand years.

Finally, and this is my magnum opus, I told them that I do not believe in a literal heaven or hell, but that I understand them as metaphors for states of mind. Those who aim to achieve eudaimonia (the good life, according to Aristotle) by acting with virtue, are by definition following most of the teachings of Jesus and reach heaven i.e. good mental health. By acting in such a way that they are humble, hardworking, charitable, honest, and grateful they free themselves of negative feelings such as guilt or low self-esteem. In contrast those who aim for nothing but short-term pleasure and self-gratification are confined to ‘hell’, in other words poor mental health, in the absence of a greater purpose such as a commitment to a long-term goal such as raising a family, and often beset with feelings of guilt and detachment from the community. So heaven, usually depicted as above us, is what we get when aim for the highest good, and hell, depicted as the lowest level of Earth, is what we get when we wallow in the depths of our basest desires.

These dialectical concepts of higher and lower are prevalent throughout Western thought. From the Ancient Greek’s eudaimonia to John Stuart Mill invoking higher and lower pleasures to justify his utilitarianism, from Isaiah Berlin’s negative and positive freedoms (positive freedom being the freedom to recognise the base desires that might impede progress to higher accomplishments) to the use of high and low in day to day language – we ‘aim high’, ‘reach up’, as opposed to the ‘pits of despair’ or ‘hitting rick bottom’.

The most powerful insight I have gained from considering Christianity this was has been the revelation that many things we consider modern ideas are in fact ancient. For example, mental health has only begun to be understood in recent decades, although has fascinated for millenia, however if my model is correct than already more than two-thousand years ago wisdom was available that identified the behaviours of excess with lower quality of life and outcomes.

And so it seems to me that God is dead, as in the old-fashioned belief in his creation, but that the Kingdom of Heaven is indeed inside us, in terms of aiming for the highest good to bring about our highest form of satisfaction and fulfilment of potential. As a society, I think we could absorb the lessons of Christianity and live our lives by the Christian code, without needing to believe in an omnipotent creator or become overtly pious. Churches could revitalise their congregations by embracing this humanist element of their faith, and whole communities so atomised and disparate in this fast-moving and bewildering modernity could be brought back together on common ground of aiming for the highest good.

I don’t think that’s a bad message to teach our children, either.